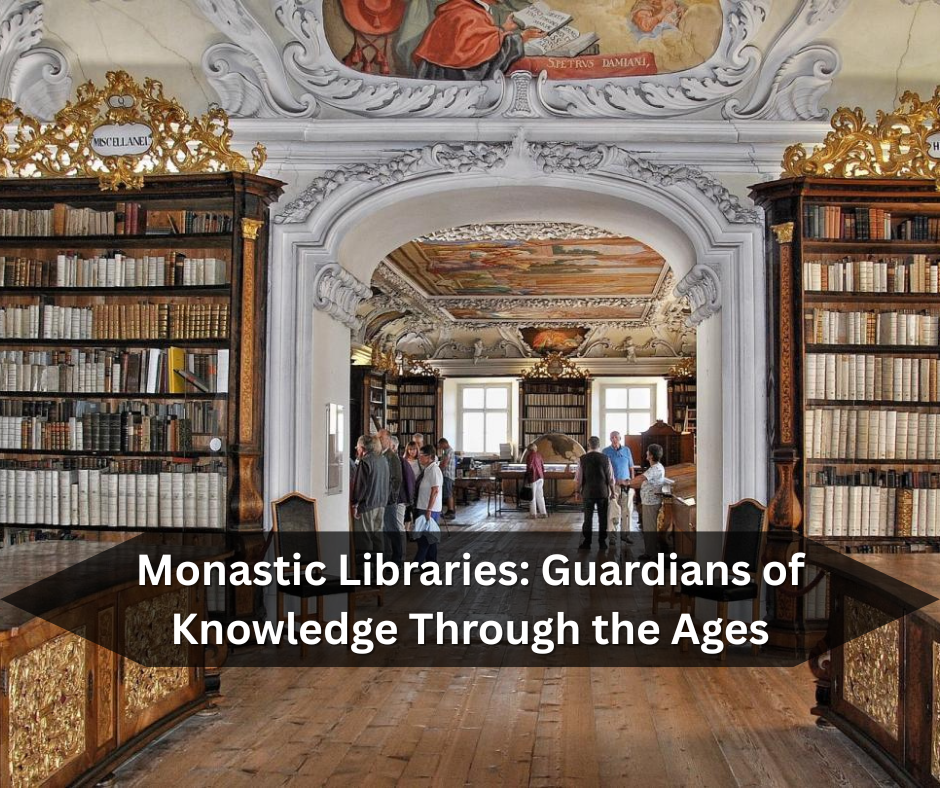

Libraries are the repositories of memory for human society, safeguarding the eternal experiences, thoughts, and feelings of generations. They preserve the ever-flowing stream of consciousness and human creativity, ensuring that knowledge and cultural heritage are transmitted across centuries. From the earliest clay tablets of Mesopotamia to illuminated manuscripts of medieval Europe, libraries have reflected both the intellectual pursuits and the artistic achievements of humanity. Among these institutions, monastic libraries hold a special place, for they were not merely collections of books but living centers of faith, culture, and learning.

The art of writing, the diverse materials used to record knowledge, and the rich traditions of manuscript illumination all found shelter within these libraries. Librarians and monastic scribes of various eras became custodians of the world’s cultural memory, carefully preserving texts at times when political turmoil or invasions threatened their destruction. Thus, monastic libraries served as beacons of light, guiding nations through dark periods, shaping intellectual traditions, and sustaining education and scholarship.

What is a Monastic Library?

The term monastic is derived from monasticism, the religious practice of withdrawing from worldly affairs to live in seclusion, prayer, and discipline, often within monasteries. A monastic library, therefore, is a library established and maintained by monks or religious communities within these monastic institutions. These libraries were created for multiple purposes: to serve the spiritual needs of the monks, to preserve sacred texts, and eventually, to advance education and scholarship.

Although not every detail about the earliest monastic libraries is known, evidence suggests that they existed in various forms across different civilizations. The earliest monastic libraries arose in Egypt, Byzantium, and Western Europe, before gradually spreading into other regions of the world. Their role was not limited to storing sacred scriptures; they also preserved secular texts, works of philosophy, classical literature, science, and history.

Origins and Early Development

The concept of monasticism is often traced to the deserts of Egypt in the 3rd and 4th centuries, where early Christian hermits sought solitude for meditation and prayer. Over time, these hermits began to form communal groups, leading to the rise of organized monasteries. With the establishment of these monasteries came the need to preserve sacred scriptures, resulting in the birth of monastic libraries.

One of the earliest known examples is a library founded by monks on the banks of the Nile River. Records mention the introduction of specific rules, often called Capitula Regularia or “rules of preservation and usage,” which governed how books were stored and accessed. The earliest known accounts describe small collections: shelves carved into monastery walls, manuscripts stacked carefully, and restrictions on how often monks or readers could access them. For instance, in one case, it is recorded that only one reader was allowed to use the library in a given week—an indication of both its sacredness and the scarcity of texts.

According to philologists and historians, Egypt housed several monastic libraries, one example being the Hellenized Coptic Monastery of Athribin in Upper Egypt, founded by Epiphanius. Another important center was the Desert of Nitria in Libya, west of the Nile Delta, where libraries flourished as part of the ascetic communities that attracted thousands of monks. These early institutions not only safeguarded Christian scriptures but also absorbed influences from Greek and Hellenistic learning.

Expansion into Europe

The tradition of monastic libraries spread beyond Egypt into Italy, Spain, France, and England, eventually becoming one of the most enduring intellectual traditions of medieval Europe.

- In Italy, between 550 and 616 CE, a significant monastic library known as the Monastic Foundation was established about 40 miles south of Genoa. This institution reflected the merging of Roman intellectual heritage with Christian monastic culture.

- In Spain, the tradition can be traced to St. Martin of Tours, who founded a monastery in 397 CE. When the African bishop Donatus fled to Spain, he brought with him both texts and monastic traditions, contributing to the rise of monastic libraries there.

- In England, the arrival of missionaries such as St. Augustine of Canterbury in the 6th century, under the direction of Pope Gregory the Great, introduced monastic learning. The Venerable Bede, one of England’s greatest scholars, noted that he saw many books and libraries in monasteries during this period, showing how far the tradition had spread.

Thus, by the 6th century, monastic libraries had become widespread, functioning as both centers of spiritual devotion and educational advancement.

The Middle Ages: Flourishing of Monastic Libraries

The Middle Ages marked the golden age of monastic libraries. Between the 9th and 12th centuries, monasteries across Europe became central to the preservation of classical and Christian texts.

- In the Middle East, one of the notable institutions was the Lombard Library, established around 565 CE, which connected monastic learning with broader Christian traditions.

- In France, the Cluny Monastery, founded in 910 CE, became one of the most influential centers of learning in medieval Europe. By the 11th and 12th centuries, Cluny’s library housed over 100 manuscripts, an impressive number for its time, making it the largest and most prestigious library in France.

- Throughout Europe, monasteries not only collected but also copied manuscripts in their scriptoria (writing rooms). Monks spent their lives copying sacred texts, classical works of philosophy, and even scientific treatises. The painstaking labor of these scribes ensured the survival of much of Greco-Roman literature, which might otherwise have been lost during Europe’s so-called “Dark Ages.”

Functions of Monastic Libraries

Monastic libraries were more than storage places; they served several key functions:

- Preservation of Knowledge – By safeguarding ancient manuscripts, they became bridges between antiquity and the Renaissance.

- Centers of Education – Monks used these libraries to train novices and scholars, keeping alive traditions of literacy when much of Europe was illiterate.

- Scriptoria and Copying – The act of copying manuscripts was considered both intellectual and spiritual labor, turning monastic libraries into centers of manuscript production.

- Cultural Transmission – These libraries maintained continuity of cultural traditions by preserving works of theology, law, medicine, philosophy, and history.

Decline and Extinction

Despite their immense importance, monastic libraries began to decline after the 12th century. Several factors contributed to this decline:

- The rise of universities, schools, and colleges created new centers of learning, shifting intellectual authority away from monasteries.

- The growth of urban culture and the emergence of secular libraries meant that monasteries were no longer the sole guardians of knowledge.

- Political upheavals and wars often led to the dispersal or destruction of manuscripts. For example, during the Protestant Reformation, many monastic libraries in England were dissolved, and their manuscripts lost.

- By the late medieval period, many monasteries themselves had been abandoned or secularized, further accelerating the extinction of monastic libraries.

Legacy of Monastic Libraries

Although their direct influence waned, the contribution of monastic libraries to human civilization remains undeniable. They not only preserved Western cultural traditions but also ensured that much of the intellectual heritage of antiquity survived long enough to inspire the Renaissance and the modern university system.

Even in their decline, they paved the way for the growth of larger and more specialized research libraries, which inherited their role as guardians of knowledge. As one scholar noted, the monks who maintained these libraries were the “real scientists” of their time—not in the experimental sense, but in their dedication to the survival of knowledge.

Conclusion

From their humble beginnings in the deserts of Egypt to their flourishing in medieval Europe, monastic libraries represent one of the most remarkable achievements in the history of knowledge preservation. They were not merely collections of sacred texts but vital instruments in shaping Western intellectual traditions.

While they eventually lost their individuality with the rise of universities and secular institutions, their contribution cannot be overlooked. Without the efforts of monastic scribes and librarians, much of the classical world’s literature, philosophy, and history would have been lost forever.

In the grand narrative of civilization, monastic libraries stand as symbols of resilience and devotion, reminding us that the survival of knowledge often depends on the quiet labor of dedicated individuals.