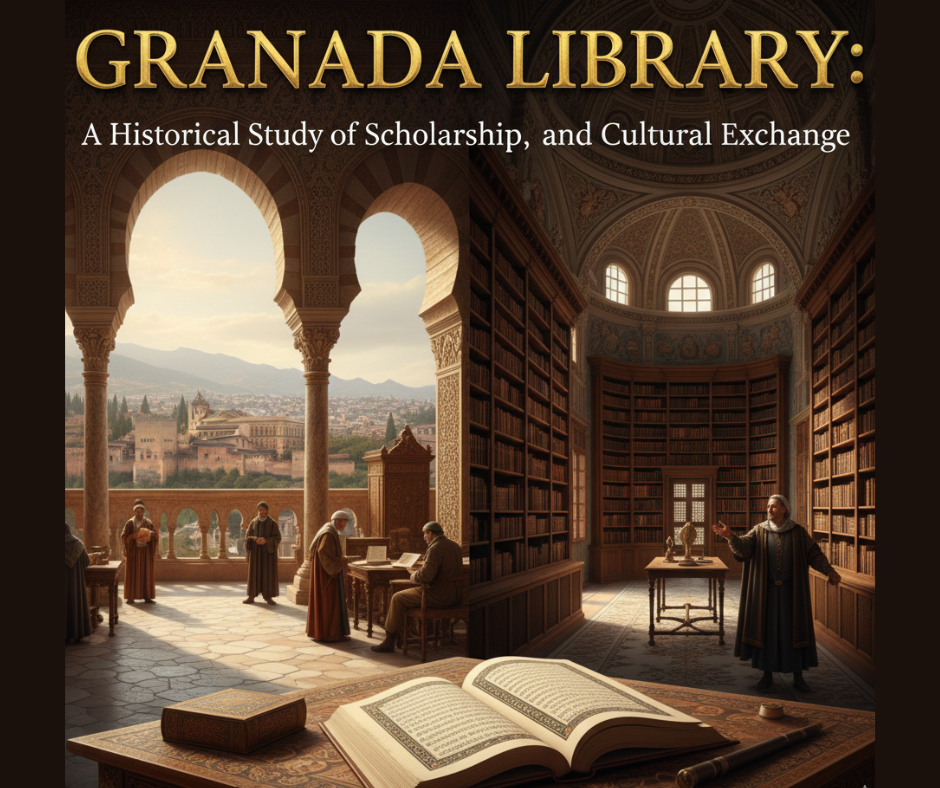

Interest in Greek literature, science, and philosophy spread far beyond the Christian world. When the Arabs expanded their empire—from Central Asia to Asia Minor, and from North Africa to Spain—they carried a strong tradition of curiosity and learning. Wherever they went, they built centers of knowledge. These included mosques with libraries, royal courts full of scholars, and busy book markets. In this large Muslim world, one of the most important centers of learning in Spain was the Granada Library.

Granada as a Center of Knowledge in Medieval Spain

Granada, a historic city in southern Spain, became a safe place for Muslim culture and learning during the last years of Islamic rule in Spain. The Granada Library was not just a building. It symbolized a community that valued knowledge more than wealth.

Arabic education spread widely in Spain during the period of Al-Andalus. This culture also influenced Christians and Jews, who learned from Arabic science and literature. As a result, cities like Toledo, Seville, and Cordoba became major centers of learning. Cordoba was one of the most famous, known for its many libraries and bookshops.

But when Christian armies slowly took back Muslim lands, Muslims moved south. Their final home became Granada, the last Muslim kingdom in Spain. Many scholars, poets, scientists, and booksellers moved there. They brought rare books and valuable manuscripts. Some historians say the number of refugees who arrived with books and knowledge was larger than the original population of educated people in Granada. This created a strong and active learning environment.

Arabic Education in Al-Andalus and the Rise of the Granada Library

The Nasrid dynasty, who ruled Granada from the 1200s to the late 1400s, supported education and culture. They encouraged scholars, poets, and scientists. Their support was similar to the famous cultural support seen in Baghdad under the Abbasids.

The Nasrid rulers competed with rulers in the Islamic East in generosity. They funded scholars, invited poets to their courts, and built beautiful buildings. Many of these buildings included libraries, classrooms, and places to copy manuscripts.

Because of their support, Granada produced many poets, scholars, and astronomers. Women of noble families also became well-known writers. Famous names include Najhun Ja’ib, Hamida, Hafsa, Al-Falah, Safia, and Maria. Their writings show how rich and active the literary culture was during this time.

Manuscripts and Knowledge Treasures of the Royal Granada Library

The royal Granada Library was a remarkable collection of manuscripts. It covered almost every area of learning, including:

- Poetry and Literature: Arabic poems, Andalusian poetry, stories, and prose.

- Languages and Grammar: Books on Arabic grammar and language studies.

- History and Geography: Records of earlier Islamic empires and descriptions of distant lands.

- Philosophy: Works related to Aristotle, Plato, and Muslim philosophers like Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina.

- Science and Mathematics: Books on algebra, geometry, astronomy, optics, and physics.

- Medicine: Texts by Hippocrates, Galen, and Muslim doctors.

- Music and Art: Manuals on musical theory and artistic styles.

- Botany and Chemistry: Books on plants, herbs, and early chemistry.

- Astrology and Astronomy: Star charts and studies of the night sky.

Granada also had many private libraries, sometimes richer than the royal one. Some well-known owners were:

- Ibn Farjun, a famous artist and book lover

- Abu al-Qasim al-Kalbi, teacher of the historian Ibn al-Khatib

- Abi Abdullah Ataraji, owner of a large manuscript collection

Another important figure was al-Zubaydi, a writer and copyist. He collected many books and created a large personal library. Later, his library was robbed by a group known as the Esquivels, showing how fragile knowledge can be during conflict.

The city also had well-known booksellers. Among them was Ibn Ballis, who helped provide books to scholars and students.

The University of Granada: A Multicultural Hub of Learning in Islamic Spain

Granada had a well-known university, sometimes called the Granada University Library. It served as both a teaching institution and a place for storing knowledge. Each department had a rector, chosen from respected scholars.

One of the most famous rectors was Sirajuddin Abu Jafar Omar al-Hakami, who served in the mid-1500s. One special feature of this university was that it did not discriminate based on religion. Educated Jews and Christians could also become rectors. This idea reflected an important belief of Andalusian Muslims:

true learning is more important than religious difference.

The atmosphere of the university was open, diverse, and full of ideas. This made Granada one of the important centers of learning in medieval Europe.

The Fall of Granada and the Tragic Destruction of Knowledge

In 1492, the Christian Reconquista ended with the fall of Granada. The peace treaty promised protection for Muslims and their institutions, but these promises were broken. The Moriscos—Muslims living under Christian rule—soon faced harsh treatment.

Arabic books were banned. Manuscripts were collected and destroyed. Libraries were burned.

According to the historian Lee, after Christians captured Granada in 1495, Cardinal Ximénez de Cisneros ordered the burning of almost 5,000 rare books. Only a few medical texts were saved. This was one of the worst losses of knowledge in Spanish history. Centuries of scholarship vanished in flames.

Legacy of the Granada Library

Although the Granada Library was destroyed, its influence continued. Knowledge preserved in Muslim Spain helped start the European Renaissance. Many works of Greek philosophy, mathematics, science, and medicine reached Europe through Arabic translations made in places like Granada, Toledo, and Cordoba.

The Granada Library stands today as a powerful reminder of a civilization that deeply respected knowledge. It shows that libraries are not just buildings filled with books—they are keepers of human memory, connections between cultures, and sources of future progress.